This is my final year project/dissertation for my degree in German and Chinese from the University of Leeds. It considers the implications for Sino-German geopolitical relations in light of the ‘new silk road’ initiative. I focus in particular on the logistics company Duisport. The text is written in German, but if there is interest I will consider translating it into English.

In diesem Blog-Post findet man meine Dissertation für meinen Germanistik- und Sinologie Abschluss. Es handelt sich um geopolitische Beziehungen zwischen Deutschland und China mit Blick auf die ‘Neue Seidenstraße’ Initiative.

Inhalt

Zusammenfassung. 3

Einführung. 3

Literaturrecherche. 4

Methodologie. 6

Kapitel 1 – was ist Ein Gürtel und eine Straße?. 7

Kapitel 2 – Alle Wege führen nach Duisburg: Geopolitische Positionierung. 9

Kapitel 3 – Duisport und Volkswirtschaft 14

Schluss. 23

Bibliographie. 24

Zusammenfassung

Die Seidenstraße ist wieder da. Chinas globales Infrastruktur Projekt wird die ganze Welt beeinflussen, aber inwiefern steht noch zur Debatte. Es besteht ein Mangel an akademischen Literatur über das Neuen Seidenstraßen (Offiziell Ein Gürtel und eine Straße genannt) Projekt und ihre Auswirkung auf Deutschland. Diese Dissertation versucht, diesen Mangel an Forschung anzugehen. Der „Gürtel“ des Projektes, der über Eurasien durchquert, hat Deutschland als seinen Endpunkt. Diese Dissertation versucht, aktuelle Implikationen und Hindernisse des Projekts hinsichtlich der deutschen und chinesischen Perspektiven zu verstehen, und konzentriert sich auf das Unternehmen Duisport in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Ein theoretischer Rahmen von den Bereichen internationalen Beziehungen und Volkswirtschaft wird auf den aktuellen Diskurs in Deutschland und China angewendet, um festzustellen, welche Herausforderungen für Deutschland bestehen. Politische Gespräche, Geschäftsberichte, und politische Dokumente werden angewendet, um die deutschen und chinesischen Perspektiven der Initiative kritisch zu analysieren. Die Forschung findet, dass Ein Gürtel und eine Straße zu engerer politischer Kooperation zwischen Deutschland und China führen könnte, aber bilaterale Unstimmigkeiten müssen zuerst gelöst werden. Die Vertiefung von multilateralen Handelsbeziehungen, die ein Kernpunkt der Initiative ist, hängt von der Erlösung der Unstimmigkeiten ab. das Gewisse Maß an Zurückhaltung gegenüber der Neuen Seidenstraßen von Deutschland ist aber sinnvoll, weil Künftige Folgen des Mega-Projekts noch schwer vorherzusagen sind.

Einführung

China will die Seidenstraße erneuen. Wie die alte Seidenstraße im Altertum soll die Ein Gürtel und eine Straße Initiative über Zentralasien durchqueren, und soll letztlich China und Europa durch neue Handelsrouten verbinden. Deutschland befindet sich ganz am Ende des neuen Gürtels. Die akademische Literatur hinsichtlich der Neuen Seidenstraßen Projektes ist bislang spärlich und aktuelle deutsche Meinung über die Initiative beruht hauptsächlich auf Furcht statt einer sachlichen Beurteilung der potenzialen Auswirkung. Die Initiative stellt sich wichtige Fragen an bilaterale wirtschaftliche und politische Beziehungen zwischen China und Deutschland. Diese Dissertation versucht, die aktuelle Wahrnehmungen und Verständnis der Initiative von sowohl der deutschen, als auch der chinesischen Perspektive sachlich zu betrachten. Dadurch werden potenziale Chancen und Risiken für Deutschland diskutiert. Die folgenden Kapitel bestehen aus einer Diskussion der Internationalen Handelsentwicklungen zwischen China und Deutschland mit Blick auf die Einen Gürtel und eine Straße Initiative und beschäftigen sich mit den geopolitischen Implikationen der Handelsbeziehungen zwischen den zwei Ländern. Der Schwerpunkt dieser Analyse liegt auf Duisburger Hafen in Nordrhein-Westfalen, wo der Gürtel seine Reise über Eurasien endet.

Literaturrecherche

Die Literatur über „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße ist bislang spärlich. Man muss sich deswegen hauptsächlich mit Aktuellen Berichten statt einer großen Menge von akademischen Sekundärquellen beschäftigen. Es folgt, dass eine sachliche Betrachtung solcher Berichte notwendig ist, um durchgreifende Forschung zu schaffen. Deswegen werden die theoretischen Werke von Denkern im Bereich internationalen Beziehungen und Volkswirtschaft bei den Texten angewendet. Die Theoretischen Texte werden später im Methodologie Abteil eingeführt.

„Visionen und Aktionen zum gemeinsamen Aufbau des Wirtschaftsgürtels entlang der Seidenstraße und der maritimen Seidenstraße des 21. Jahrhunderts“ (Staatliche Kommission. 2015) ist der Text aus China, der Ziele für die neuen Seidenstraßen erzählt. Dabei ist es notwendig zum Verständnis der aktuellen Entwicklungen und Beziehungen hinsichtlich des Projekts. Er stellt Chinas bis ab 2015 entwickeltes Rahmen für die Initiative fest. Dieser Bericht stellt eine Zukunft vor, in der Eurasien und Afrika nicht nur durch Handelsrouten verbunden sind, sondern auch durch wirtschaftliche sowie politische Ziele vereinigt sind. Er zeigt die umfassende Natur des Plans, aber erzählt nichts darüber, wie die Ziele erreicht werden können. Betont sind Zusammenarbeit beteiligter Staaten, freier Handel und umfassende Entwicklung durch friedliche Art und Weise.

Die deutsche Regierung Stellt die Entwicklung zwischen den Ländern als positiv dar, und fordert enge Zusammenarbeit. (Das Auswärtige Amt. 2014) Handelsvolumen und bilaterale Investitionen steigern, aber die Regierung hat Bedingungen für engere Zusammenarbeit, einschließlich die Verbesserung der Menschenrechte in China. Einige ExpertInnen weisen darauf hin, dass die maritime Seidenstraße Initiative auch nach Europa führt. (Schüller Und Nguyen. 2015) Man kann sehen, dass China und Deutschland nicht nur über Land durch den Gürtel verbunden sein werden, sondern auch durch die neuen Maritimen Routen. Schüller und Nguyen betonen die Verbindung zwischen die Initiative und die soft power- Politik Chinas. Auch werden die Ziele und Instrumente der Initiative diskutiert. Es besteht dazu Implikationen für die sino-deutschen wirtschaftlichen Beziehungen. Erber (2013) weist auf Gründe bezüglich der Wirtschaft für potenzialen Streit zwischen den Ländern hin, nämlich Deutschlands komparativen Vorteil im Bereiche Hoch- und Spitzentechnologie, Bedrohung auf die deutsche Autoindustrie, Dumpingpreise und das erwartete Scheitern der chinesischen Wirtschaft. Es ist jedoch wichtig zu anerkennen, dass die Situation hat sich seit 2013 verändert. Chinesische Anleger Klagen inzwischen vor, dass Deutschland allmählich protektionistisch wird. (China International Investment Promotion Agency. 2017) Einige behaupten, dass Deutschland in einer Verordnung von Juli 2017 Investition Interesse aus nicht-EU Länder beeinträchtigt, und dass das deutsche Investitionsumfeld sich verschlechtert hat. Der Kommentar stellt sich im Gegensatz zur Behauptung, dass China Freien Handel abschließt.

Deutsche ExpertInnen gegenüber sino-deutsche Beziehungen bieten eine sachliche Betrachtung und Bewertung des „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ Projekts. Godehardt (2016a) weist auf die Bedeutung von ‚Großen Visionen‘ in der chinesischen Politik und, wie die westliche Betrachtung darauf als ‚leere Floskeln‘ eine Unterschätzung ist. Beispiele davon sind Deng Xiaopings ‚Friedliche Entwicklung‘, Hu Jintaos ‚Harmonische Gesellschaft‘ und Xi Jinpings ‚Chinesischen Traum‘. Mit Blick auf „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ „bleibt diese Vision imaginär und diffus, und dennoch – oder gerade deshalb – stellt sie ein wichtigen Orientierungs-Punkt für chinesische Entscheidungsträger dar“ (Ibid.). Godehardt argumentiert, das Projekt sei ein wirtschaftliches, politisches, kulturelles Netzwerk mit globaler Ausdehnung. Es versuche nicht, einen umfassenden Plan festzulegen, und stelle stattdessen ein biegsames Konzept dar, in dem mehrere Formate von Zusammenarbeit zusammen existieren und funktionieren können. Auch diskutiert wurde die transregionale Auswirkung der Initiative (Godehardt. 2014). Der Gürtel wird über Zentralasien und Osteuropa durchqueren, und wird Deutschland deshalb geopolitisch betreffen. Es wird betont, dass die Bedeutung politischer Grenzen zwischen Zentralasien, dem Kaukasus, dem Schwarzmeer Gebiet und Europa mindestens in der chinesischen Politik reduzieren wird.

Ein Kernpunkt in den schnell entwickelnden Beziehungen gegenüber „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ liegt in Nordrhein-Westphalen, nämlich Duisburger Hafen. Presse Mitteilungen von Duisport zwischen 2016 und 2017 leuchten die Beziehung zwischen China und Duisport ein. Sie betonen den vorteilhaften geopolitischen Standpunkt des Hafens und die schnelle Entwicklung bilateraler Handelsbeziehungen zwischen dem Hafen und Urumchi im westlichen China. (Duisport. 2016c) Sie geben Einblick in der Bedeutung der deutschen Logistik hinsichtlich des „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ Projektes als Verkehrsmittel für Handel sowie Kultur. (Duisport. 2017b; 2017c; 2017d) Man muss dennoch aufmerksam sein, da die Mitteilungen versuchen, die Position Duisport zu verstärken, und dabei bieten keinen ausgewogenen Standpunkt an. Duisport richtet sich deutlich im Geschäftsbericht von 2016 an „ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ aus. Der Hafen stellt sich selbst als Drehschiebe nicht nur der deutschen, sondern auch der europäischen Markt dar, und betont die schon weitentwickelte Beziehung zwischen Duisport und China (Duisport. 2016b). Das E-Commerce verdient im Bericht besondere Aufmerksamkeit. China besteht den größten E-Commerce Markt und das Geschäft will sich an den stark gewachsenen Markt ausrichten. Der Bericht zeigt auch deutlich, wie Duisport mit der deutschen Politik stark verbunden ist. Beim 300 Jahr Jubiläum des Hafens wurde eine Mehrzahl von Politikern eingeladen. Diese Verbindung wird in den Presse Mitteilungen von Duisport sowie politische Gespräche von Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel und Außenminister Sigmar Gabriel auch deutlich gesehen.

Auch von besonderer Bedeutung ist die chinesische Logistik Firma Cosco. Der Cosco halbjährliche Bericht von 2017 fasst die im letzten Jahr entwickelten Geschäftstätigkeit Coscos zusammen. Er gibt einen Einblick in der geopolitischen Positionierung chinesischer Logistik bezüglich „ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ und trägt dabei ein tieferes Verständnis der chinesischen Herangehensweise an Wirtschaftsbeziehungen mit Deutschland sowie die gesamte Welt. (Cosco. 2017) Cosco ist ein chinesischer Staatseigener Betrieb und deswegen gibt es eine Möglichkeit, eine Verbindung zwischen dem Betrieb und politischen Interessen des chinesischen Staates zu bestehen. Der Bericht erzählt keinen bestimmten Plan für eine entwickelte Zusammenarbeit mit dem deutschen Markt, aber ein umfassendes Bild kann von der bestehenden Informationen extrapoliert werden.

Deutschland steht vor dem Projekt ohne Einstimmigkeit. Politische Gespräche von Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel sowie Außenminister Sigmar Gabriel zeigen die Komplexität der aktuellen politischen Beziehung zwischen China und Deutschland mit Blick auf die neuen Seidenstraßen. Frau Merkel scheint sich positiv ans Projekt zu agieren, aber sie betont, dass China im Rahmen internationalen Richtlinien „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ entwickeln soll (Die Bundesregierung. 2017). Es besteht Zweifel an der Einstellung Sigmar Gabriels. Bei der 25. Französischen Botschaftskonferenz hat Gabriel seine Sorgen um das Projekt ausgedrückt (Gabriel. 2017a). Europa werde allmählich schwächer, während China wachse. Er glaubt, die Initiative sei teilweise ein wirtschaftlicher Plan, aber es werde gleichzeitig geopolitisch und sogar militärisch geprägt. Trotzdem war der Außenminister 17 Tage Später in Beijing bei der Ausstellung „Deutschland8“, um die sino-deutsche Beziehungen zu loben. (Gabriel. 2017b)

Methodologie

Ein theoretischer Rahmen aus dem Bereich Volkswirtschaft und internationale Beziehungen wird bei den Berichten von Unternehmen angewendet, um bilaterale volkswirtschaftliche Implikationen der neuen Seidenstraße besser zu verstehen und beurteilen. Ein theoretischer Rahmen hilft jedoch nicht, „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ in einem aktuellen soziokulturellen Umfeld einzufügen. Deswegen zieht diese Dissertation auf Sekundärquellen von Experten sino-deutscher Beziehungen, und analysiert sie von einem vornehmlich konstruktivistischen Standpunkt. Wendts (1992) Anerkennung, dass Machtpolitik gesellschaftlich konstruiert und deswegen sozial- und kulturell geprägt ist, trägt zum Verständnis bei, warum China und Deutschland unterschiedliche Wahrnehmungen der neuen Seidenstraßen haben. Eine Mehrzahl der Implikationen für Deutschland existiert in diesem gesellschaftlich konstruierten Umfeld.

Eine Erörterung einer kleinen Anzahl von politischen Gesprächen und der Handlung eines einzigen Unternehmens ist nicht genügend, das Gesamtbild der Einwirkung auf Deutschland von der neuen Seidenstraße zu repräsentieren. Andere Unternehmen und ein weitreichenderes politisches Umfeld müssen geforscht werden, aber weitreichendere Analyse liegt aus dem Anwendungsbereich dieser Dissertation. Man soll sich trotzdem nicht entweder mit Politik oder Handel beschäftigen, weil Politik und Wirtschaft eng verbunden sind (Gilpin. 2001). Diese Verbindung ist mit Blick auf „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ deutlich, und muss berücksichtigt werden. Es ist mindestens notwendig, den weiten politischen Hintergrund darzustellen, um die Vielschichtigkeit des Chinesischen Projektes und seiner Auswirkung zu dekonstruieren.

Kapitel 1 – was ist Ein Gürtel und eine Straße?

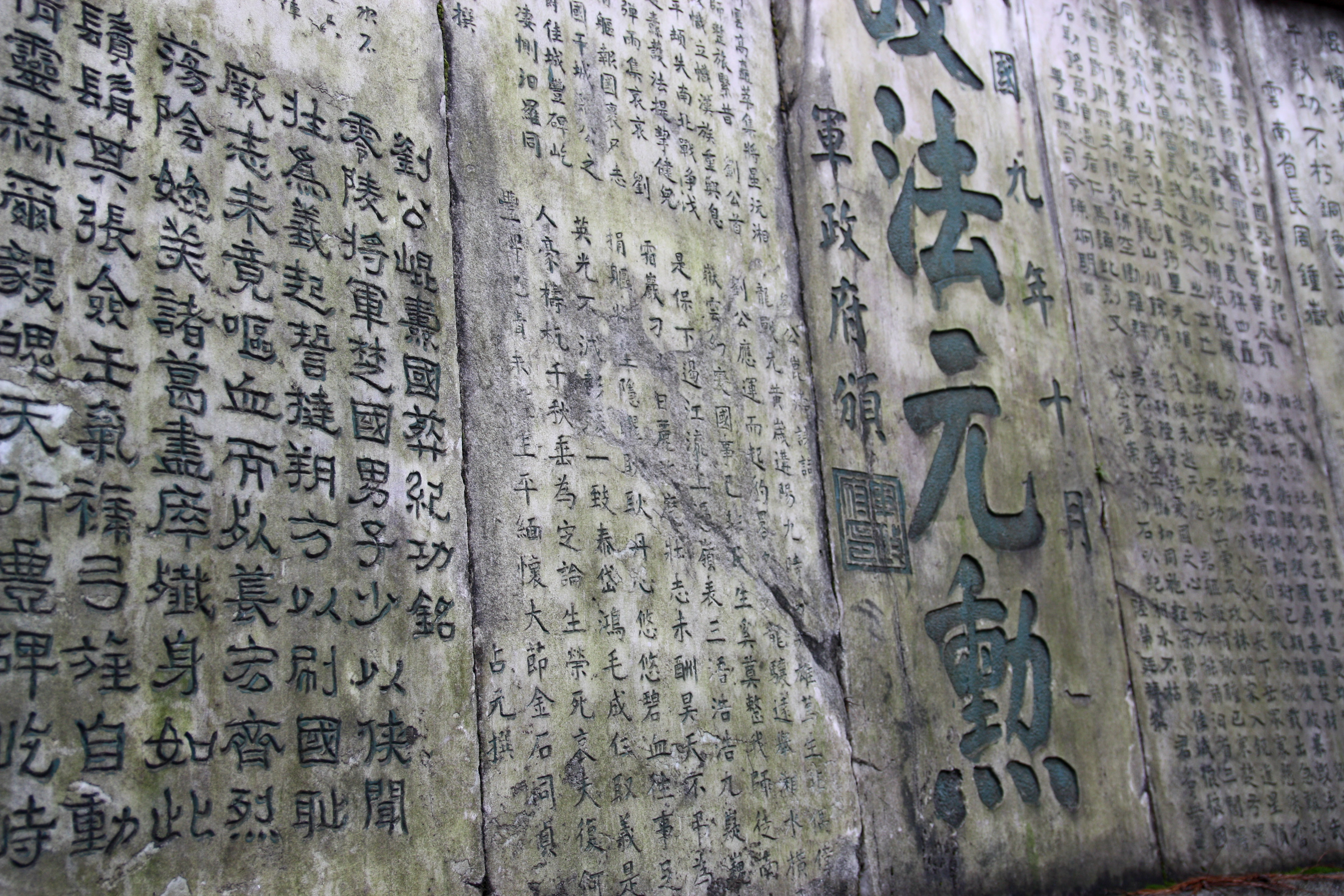

Ein Gürtel und eine Straße wurde 2013 von Chinesischen Staatspräsident Xi Jinping in Kasachstan angekündigt (The History of Commerce. Kein Datum). Er sprach von einem goldenen Zeitalter vor über 2000 Jahren, in dem Ostasien durch die Seidenstraße über Zentralasien mit Europa verbunden war (Xi. 2013). Ein Gürtel und eine Straße soll laut Xi Jinping eine „neue Seidenstraße“ sein, die internationale politische, wirtschaftliche und menschliche Prinzipien fördert (Ibid.). Das Projekt erscheint hauptsächlich wirtschaftlich geprägt zu sein, und wird ursprünglich in dieser ersten Ankündigung den „neue Seidenstraße Wirtschaftsgürtel“ genannt (Ibid.). Politische Positionierung ist auch ein wichtiger Faktor. Die Verstärkung von politischer Kommunikation ist der erste Aspekt, den Präsident Xi in seinem 2013 Gespräch erwähnt, dass international verbessert werden soll (Ibid.). Was in Kasachstan jedoch fehlt, war ein konkreter Plan.

Laut Visionen und Aktionen zum gemeinsamen Aufbau des Wirtschaftsgürtels entlang der Seidenstraße und der maritimen Seidenstraße des 21. Jahrhunderts, Der Haupttext von der chinesischen Regierung über die Neuen Seidenstraßen, ist das Ziel des Projektes, freie Zirkulation von Wirtschaftsfaktoren, effiziente Verteilung von Ressourcen und Integration von Märkten zu fördern (Staatliche Kommission für Entwicklung und Reform. 2015). Dazu soll es Länder ermutigen, ihre Wirtschaftspolitik zu koordinieren, um allen Beteiligten Ländern zugutekommen zu lassen (Ibid.). „Konnektivität“, „Friedliche Koexistenz“, „Harmonie“, und „ Inklusion“ sind Konzepte, die als Kernpunkte des Projektes dargestellt werden (Ibid.) und sind Faktoren, die in den folgenden Kapiteln ausführlich diskutiert werden. Der wichtigste Punkt ist vorerst aber der deutliche Mangel an einem greifbaren Plan. Offizielle Information enthüllt nur Konzepte, die politische Ideale statt eines durchführbaren Plan ähneln. Die Neuen Seidenstraßen wurden teilweise deswegen für eine lange Zeit in Europa nicht ernst genommen.

Das Projekt ist aber tiefernst gemeint. Beim neunzehnten nationalen Volkskongress Chinas 2017 hat Präsident Xi seine Position gegenüber „Einen Gürtel und eine Straße“ weiter befördert (Xi. 2017b). Der nationale Kongress ist die wichtigste politische Veranstaltung in China, und gesprochen werden nur die wichtigsten Themen in der chinesischen Politik. Die im Kongress angewendete Rhetorik gegenüber die neuen Seidenstraßen lässt sich zu Xis früheren Gesprächen ähneln. Es besteht keine Erwähnung von geplanten Routen oder politischen Vereinbarungen, aber das Konzept bleibt Kohäsiv. Mit der Erwähnung des Projektes beim nationalen Kongress soll Europa jetzt verstehen, dass China das Ziel von den neuen Seidenstraßen sehr ernsthaft verfolgt.

Ein gezielter Endpunkt lässt sich in Xis Gesprächen mindestens zeigen. Das Ziel heißt Europa. Präsident Xi hat 2013 in Kasachstan schon seine große Vision vorgestellt, in der Ostasien mit Europa durch Zentralasien verbinden lässt. (Xi. 2013) Wie dieser Text zeigen wird, liegt der genaue Endpunkt in Deutschland. Der Mangel an einem von chinesischen Regierung vorgeschlagenen Plan, um die Verbindung zu schaffen, scheint in der Wirklichkeit keine Rolle zu spielen, da neue Handelsrouten und politische Vereinbarungen schon im Aufbau sind. Durch den Shanghaier Organisation für Zusammenarbeit (SOZ) hat China zum Beispiel schon bilaterale Kooperationsmechanismen mit jedem zentralasiatischen Land etabliert (Godehardt. 2014, s.10). Der Plan ist gewissermaßen, keinen Plan zu haben, und stattdessen flüssig und Pragmatisch zu sein.

Es ist wichtig kurz zu überlegen, warum China dieses Megaprojekt durchführen will. Von der offiziellen chinesischen Perspektive gibt es zwei Hauptgründe für das Projekt: erstens die Regulierung von Investition und Handel in multilateralen Rahmen (Staatliche Kommission. op. Cit.), und zweitens als Folge vom „Trend der Multipolarisierung der Welt, der wirtschaftlichen Globalisierung […] und der Informatisierung der Gesellschaft“ (Ibid.). Die zwei Gründe stellen jeweilig volkswirtschaftliche und geopolitische Fragen dar, und es besteht Zweifel daran, ob die offiziellen Gründe die Realität entspricht. China könnte zum Beispiel durch die Entstehung von neuen Institutionen wie die Asiatische Infrastruktur-Investitionsbank oder durch politischen Einfluss auf westlichen Unternehmen die bestehenden internationalen Ordnungsstrukturen unter Druck setzen. Mit Verweis auf die oben durchgeführte Diskussion über die Neue Seidenstraßen ist es jetzt möglich, die Diskussion über ihre potenziale Auswirkung auf Deutschland mit Blick auf Geopolitik und Volkswirtschaft zu beginnen.

Kapitel 2 – Alle Wege führen nach Duisburg: Geopolitische Positionierung

Brzezinski betrachtet Eurasien als geopolitisch axial (Brzezinski. 1997). Wer Macht über Eurasien verfügt, kontrolliere die ganze Welt. Deswegen hält die deutsche Regierung die Neuen Seidenstraßen in Verdacht. Die derzeitige Weltordnung sieht unsicher aus. Die Vereinigten Staaten vernachlässigen wegen ihrem nach innen gerichteten Präsidenten globale Angelegenheiten, und Brexit droht inzwischen die Stabilität der europäischen Union zu belasten. Während dieser Unsicherheit hat China begonnen, die neuen Seidenstraßen schneller zu bauen. Nicht alle in Deutschland machen sich aber Sorgen um das Projekt. Für viele repräsentiert es eine Riesenchance. Dieses Kapitel versucht, Implikationen von der geopolitischen Positionierung über Deutschland zu verstehen, und dadurch festzustellen, inwiefern ein Gürtel und eine Straße geopolitische Strukturen in Deutschland verändern könnte.

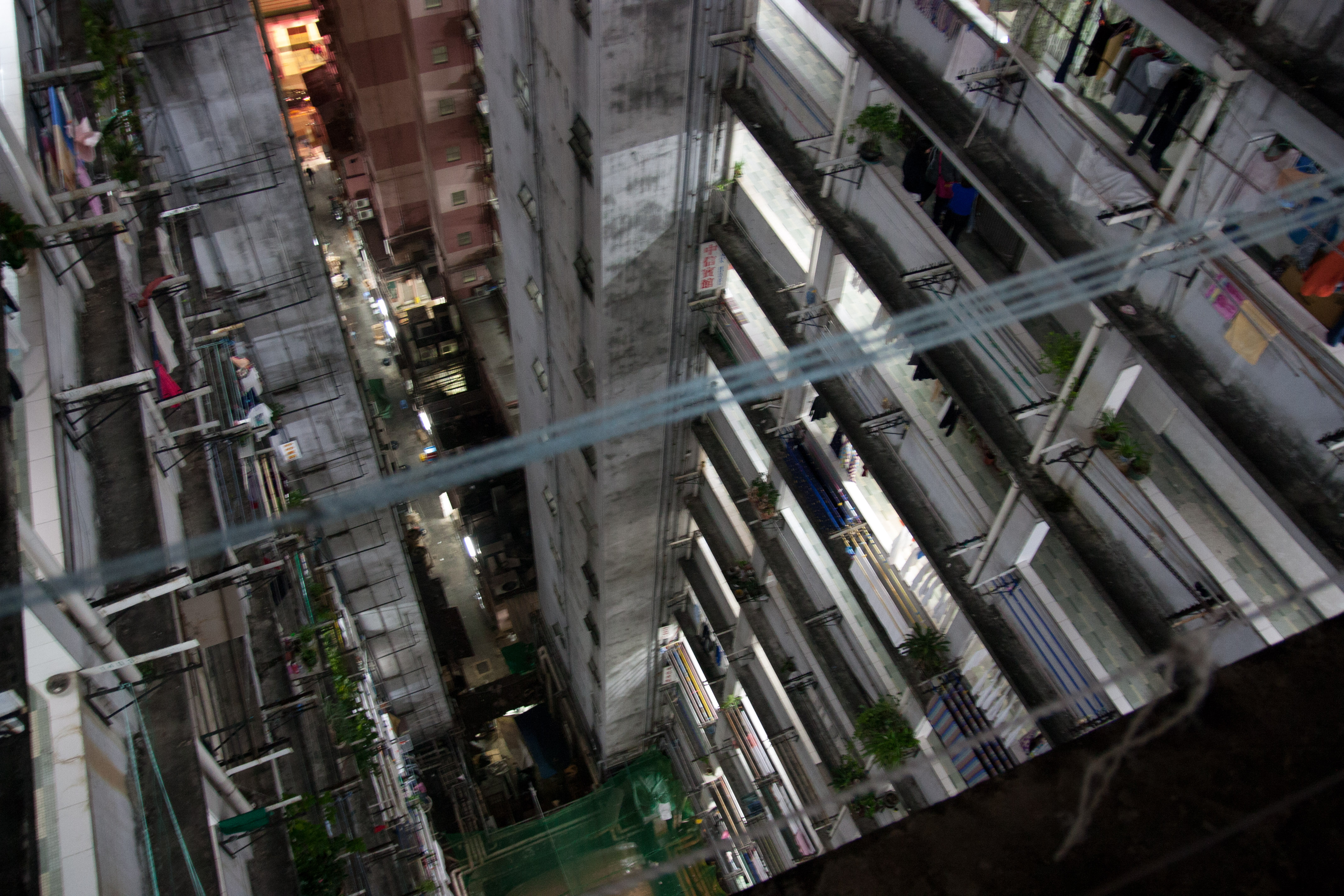

Duisburger Hafen in Nordrhein-Westfalen versucht ein Kernpunkt für die neuen Seidenstraßen zu werden. Sowohl der Land-„Gürtel“, als auch die See-„Straße“ sind mit Duisburg verbunden. Über Land sind Duisport und die chinesische Riesenstadt Chongqing schon durch Eisenbahnstrecken verbunden. Güterzüge fahren seit 2013 zwischen den zwei Standorten, die sich fast auf gegenüberliegenden Enden von Eurasien befinden (Duisport. 2013). Duisport ist auch mit den Häfen in Südeuropa verbunden, die Endpunkte der maritimen Straße darstellen (Duisport. 2017a). Andere deutsche Unternehmen wie DHL und deutsche Bahn sind auch an einem Gürtel und einer Straße beteiligt (DHL. 2015; Dbahn. 2017). Von der chinesischen Seite muss man das staatseigene Unternehmen Cosco betrachten. Cosco hat Einfluss sowohl in Duisburg, als auch Häfen überall in Europa, weil das Unternehmen immer mehr europäische Häfen übernimmt. insbesondere besitzt der Betrieb viel Einfluss in den südeuropäischen Häfen, die mit Duisport verbunden sind (Cosco. 2017a).

Duisport ist ein Logistikunternehmen, das in Nordrhein-Westfalen am Rhein liegt. Das bedeutet laut dem Unternehmen, dass sein geopolitischer Standort ideal als Standpunkt für einen Ausbau der europäischen Logistik ist (Duisport. 2016b, s.10) Der Hafen ist der größte Binnenhafen in Europa und er spezialisiert sich unter anderem auf Automobil-logistik. Duisport befindet sich deshalb in einer starken Position in den sino-deutschen Handelsbeziehungen, weil die deutsche Autoindustrie einen großen Teil der deutschen Wirtschaft macht, während Nachfrage nach deutschen Autos in China groß ist. „When you are in Duisburg, you are in Europe“(Duisport. 2016c) war die gewagte Behauptung von Duisport in einer offiziellen Aussage über Fortschritte in seinen Beziehungen mit chinesischen Wirtschaftszentren. Das Unternehmen stellt sich als einer der wichtigsten Punkte auf den neuen Seidenstraßen und als Drehscheibe für den europäischen Markt vor (Duisport. 2016b). Die Yuxinou Bahnstrecke zwischen Duisport und Chongqing existiert seit 2014 (HKTDC. 2015), aber Duisport hat schon seit 2013 eng mit China zusammengearbeitet (Duisport. 2013). Man muss aber fragen, ob Duisport wirklich ein idealer Standort ist. Die chinesische Regierung arbeitet zum Beispiel auch sehr stark mit Polen (Van der Putten. 2016, s.9) und Griechenland (Op. Cit. s.4). Lodz in Polen richtet sich an der Landroute der Neuen Seidenstraßen ähnlich wie Duisport, und sieht sich selbst auch als Drehschiebe des europäischen Markts (Op. Cit. s.9). Lodz stellt verfügt jedoch nicht über genügend Infrastruktur, um mit Duisport auf kurze Sicht erfolgreich konkurrieren zu können. Es ist bestimmt vorteilhaft für China, Deutschland als europäisches Zentrum der neuen Straßen zu haben, weil China der wichtigste Wirtschaftspartner Deutschlands in Asien ist (Auswärtiges Amt. 2017). Deutschland ist gleichzeitig Chinas wichtigster Handelspartner in Europa (Ibid.). Diese Beziehung sollte nicht unterschätzt werden, da politisches Gewicht den wirtschaftlichen Beziehungen folgt. Politik und Wirtschaft sind eng verbunden, und die Funktion der Wirtschaft wird vom Markt und der Politik bestimmt (Gilpin. 2001. S.24). Als wichtige Handelspartner sind China und Deutschland nicht nur verpflichtet, politisch eng zusammenzuarbeiten, sondern auch gut positioniert, Kooperation effektiv zu vertiefen. Das bedeutet aber mehr gegenseitige Verantwortung, die sehr positive bilaterale Beziehungen benötigt.

Duisports geographische Lage am Rhein ist von hoher Bedeutung. Der Fluss hat seit Jahrhunderten Bedeutung für die europäische Wirtschaft und fließt durch einige der wohlhabendsten Regionen Europas. Der Rhein fließt zum Beispiel nach die Niederlande, und das ist auf zwei Weisen signifikant. Erstens gehen 91% der niederländischen Exporten nach Deutschland, und allein 43% davon nach Nordrhein-Westfalen, wo Duisport liegt (Centraal bureau voor de statistiek. 2016). Dadurch öffnet sich ein großer Teil des niederländischen Marktes für China. Zweitens führt der Rhein nach Rotterdam, eine Stadt, die von Cosco als wichtiger Standort für die neuen Seidenstraßen dargestellt wird (Cosco. 2017b). Die Handelsbeziehung zwischen China und den Niederlanden entwickelt sich schneller als alle andere chinesische bilaterale Handelsbeziehungen (Den Butter & Hayat. 2008) und engere logistische Verbindungen durch Deutschland können potenziell die Entwicklung weiter vorantreiben. Duisport lässt sich als europäische Drehschiebe darstellen, und die Verbindung zwischen Duisport und Rotterdam untermauert diese Behauptung, weil Duisport als Eingangspunkt für andere Teile des europäischen Marktes dient. Es besteht jedoch die Frage, ob der Rhein eine wirksame Handelsroute ist. Obwohl der Rhein in der Vergangenheit eine wichtige Handelsroute war, hat er seit langem seine Blütezeit überschritten. China fördert neuen Bahnverkehr teilweise wegen der relativen Effektivität von Bahnverkehr im Vergleich zu Schiffsverkehr. Die historische Bedeutung des Rheins muss deshalb für China der Hauptpunkt sein. Zudem konzentriert sich China auf historisch signifikante Handelsregionen. Außer dem Rhein zielt China auf andere historisch geprägte Handelsrouten wie die Routen zwischen China und Malaysia und natürlich die Seidenstraßen selbst. Xi Jinping hat seit dem Treffen im Jahr 2013 in Kasachstan kulturell-historische Gemeinsamkeiten betont, um potenzielle Handelspartner von der Bedeutung der neuen Seidenstraßen zu überzeugen (Xi. 2013), und die Konzentration auf historische Handelsrouten ist eine Ausdehnung dieser Rhetorik.

Die Landroute des Projekts erfordert eine weite Entwicklung von Eisenbahnrouten über Eurasien und Duisport reagiert schon darauf. 2016 fahren 20 Züge pro Woche zwischen Duisburg und China (Duisport. 2016c). Im Zeitraum zwischen 2012 und 2016 hat sich die Transportzeit zwischen Deutschland und China von 19 Tagen auf 12 verkürzt (Duisport. 2016b. s.87). Effizienz ist die Hauptfrage, die die Wirtschaftlichkeit der neuen Seidenstraßen bestimmt. Ob Güterzüge effizienter als Flug- und Schiffverkehr sein könnte, determiniert den Erfolg des Projekts, und die verkürzte Transportzeit zeigt das Potenzial, bahnverkehr über die Landroute der Neuen Seidenstraßen wirtschaftlich effizienter zu werden. Nicht nur Bahnrouten zwischen China und Duisport sind wichtig. Von Duisport gibt es Routen nach Großbritannien, Norddeutschland, und die Häfen in Südeuropa. Das Schienennetz in Deutschland ist das viertbeste Netzwerk in Europa mit 33.300km von Scheinen (Bmvi. 2017), und in Kombination mit den vielen Anbindungen mit Nachbarländern ist Duisport gut positioniert, ein wichtiger Punkt in Europa für die Neuen Seidenstraßen zu werden. Die Position ist aber abhängig von der Entwicklung von Infrastruktur in den Ländern entlang der Landroute zwischen Deutschland und China wie Polen, Weißrussland und Kasachstan.

Im Jahre 2017 hat Duisport versucht, eine engere Handelskooperation mit der chinesischen Stadt Yiwu zu vereinbaren. Die Stadt liegt in der Nähe von Shanghai und ist das wichtigste chinesische Zentrum für kleine Waren und E-Commerce (The Guardian. 2017). Zwei Drittel aller Weihnachtsprodukte werden zum Beispiel in Yiwu produziert, was die Bedeutung des Standorts in Yiwu zeigt (Ibid.). Güterzüge fahren seit 2014 zwischen Duisburg und Yiwu, aber die Anzahl stieg in letzter Zeit deutlich an (Duisport. 2017b). Wie wichtig ist die Markt in Yiwu? Es ist nicht nur Duisport, sondern Länder aus der ganzen Welt, die jetzt an Yiwu konvergieren. Die Stadt hat seit Mitte der 2000er Jahre insbesondere nordafrikanische Länder angelockt (Belguidoum & Pliez. 2015), und das lässt sich darauf hindeuten, dass die Stadt wirtschaftlich sowie geopolitisch signifikant ist. Der Grund dafür ist E-Commerce. China ist der weltgrößte E-Commerce Markt und Yiwu ist das Zentrum des Marktes. Der Begriff ‚kleine waren‘ umfasst vielfaltige Artikel wie Schmuck, Dekorationen, Haushaltswaren und kleine elektronische Geräte (Ibid.), die einen signifikanten Teil des globalen E-Commerce Markt umfassen. Der deutsche E-Commerce Markt steigt auch jährlich an, (Statista. 2018) und die Vertiefung der Vereinbarung zwischen Yiwu und Duisport könnte die Bedeutung von E-Commerce in Deutschland entwickeln. E-Commerce ist abhängig von effizienter Logistik, und Duisport positioniert sich, um die Rolle von effizientem Logistiker zu erfüllen. Als deutsches Logistikunternehmen sind die potenziellen Gewinne für Duisport hoch, aber es ist schwieriger zu bestimmen, inwiefern die Beziehung zwischen Duisport und Yiwu den deutschen Markt verbessern könnte. betrachtet man das wachsende Interesse an E-Commerce in Deutschland, sollte eine engere Anbindung mit Yiwu eine positive Entwicklung sein, aber Logistiker wie Duisport sind die unmittelbar Begünstigten.

Yiwu ist aber bei weitem nicht die wirtschaftlich stärkste Stadt Chinas. In einer Liste von den 35 wirtschaftlich stärksten Städten Chinas wurde Yiwu nicht erwähnt (Dejardins. 2017). Der Hauptgrund für engere Zusammenarbeit zwischen Duisport und Yiwu muss etwas anders als wirtschaftliche Gewinne einschließen. Als Logistikunternehmen profitiert Duisport von den Handelsrouten zwischen Yiwu und Duisburg viel mehr als von der Stadt Yiwu allein. Eine Verbindung mit Yiwu ist eine Route über ganz China, und eine Handelsverbindung mit der wohlhabendsten Region Chinas, die Ostküste. Dadurch wird Duisport nicht nur mit einer relativ kleinen chinesischen Stadt angebunden, sondern auch mit dem Wirtschaftsmotor Chinas. Wenn man aber bedenkt, dass Yiwu in der Nähe von Shanghai liegt, stellt es sich die Frage, warum Eisenstrecken notwendig sind. Luft- und Schiffverkehr ist sehr gut entwickelt in Shanghai, und die Entwicklung von Eisenstrecken ist nur gerechtfertigt, wenn sie viel effizienter als die existierenden Methoden sind.

Duisport richtet sich auch an die Seestraße, und dabei außer der Grenzen von Deutschland. Juni 2017 wurde eine Zusammenarbeit zwischen Italiens größtem Adria- Hafen Triest und Duisport vereinbart (Duisport. 2016b. s.90). Das Unternehmen hat auch im Jahre 2016 mit dem größten türkischen Logistiker Arkas Holding ein Joint Venture angekündigt, das dazu führt, einen Logistik-Hub bei Istanbul gegründet zu werden (Ibid.). Duisport betonte die geopolitische Signifikanz von diesen Vereinbarungen hinsichtlich der neuen Südlichen Seidenstraße und weist auf Istanbuls Position unmittelbar an der Seeroute der neuen Seidenstraße hin (Ibid.). Triest wurde inzwischen mit Duisport durch Bahnverbindungen enger angebunden. (Ibid.) Dadurch verbindet Duisport die nördlichen Landrouten sowie die südlichen Seerouten, und wird ein wichtiger Punkt für beide die Land- und Seerouten.

Das chinesische staatseigene Unternehmen Cosco ist mit Bezug auf den Neuen Seidenstraßen auch ein wichtiger Akteur im Mittelmeer. Das Unternehmen hat Akquisitionen rund um Europa durchgeführt. Cosco hat beispielweise einen großen Teil des griechischen Hafens von Piräus übernommen (Cosco. 2017a. s.13). Seit der Übernahme von 51 Prozent im Jahre 2016 hat Cosco den Hafen schnell entwickelt, und hat 2018 einen 620 Millionen USD Entwicklungsplan enthüllt (Glass. 2018). Das Geld, das im Hafen investiert wird, zeigt wie wichtig Piräus für Coscos geostrategische Positionierung ist. Cosco hat durch seine Position in Piräus Einfluss auf eingehenden und ausgehenden Schiffverkehr im Mittelmeer. Darüber hinaus ist es höchst bedeutsam, dass Cosco im Besitz des chinesischen Staats ist, weil alle Entscheidungen des Unternehmens nicht nur Geschäftliche, sondern auch als politische Entscheidungen betrachtet werden sollen.

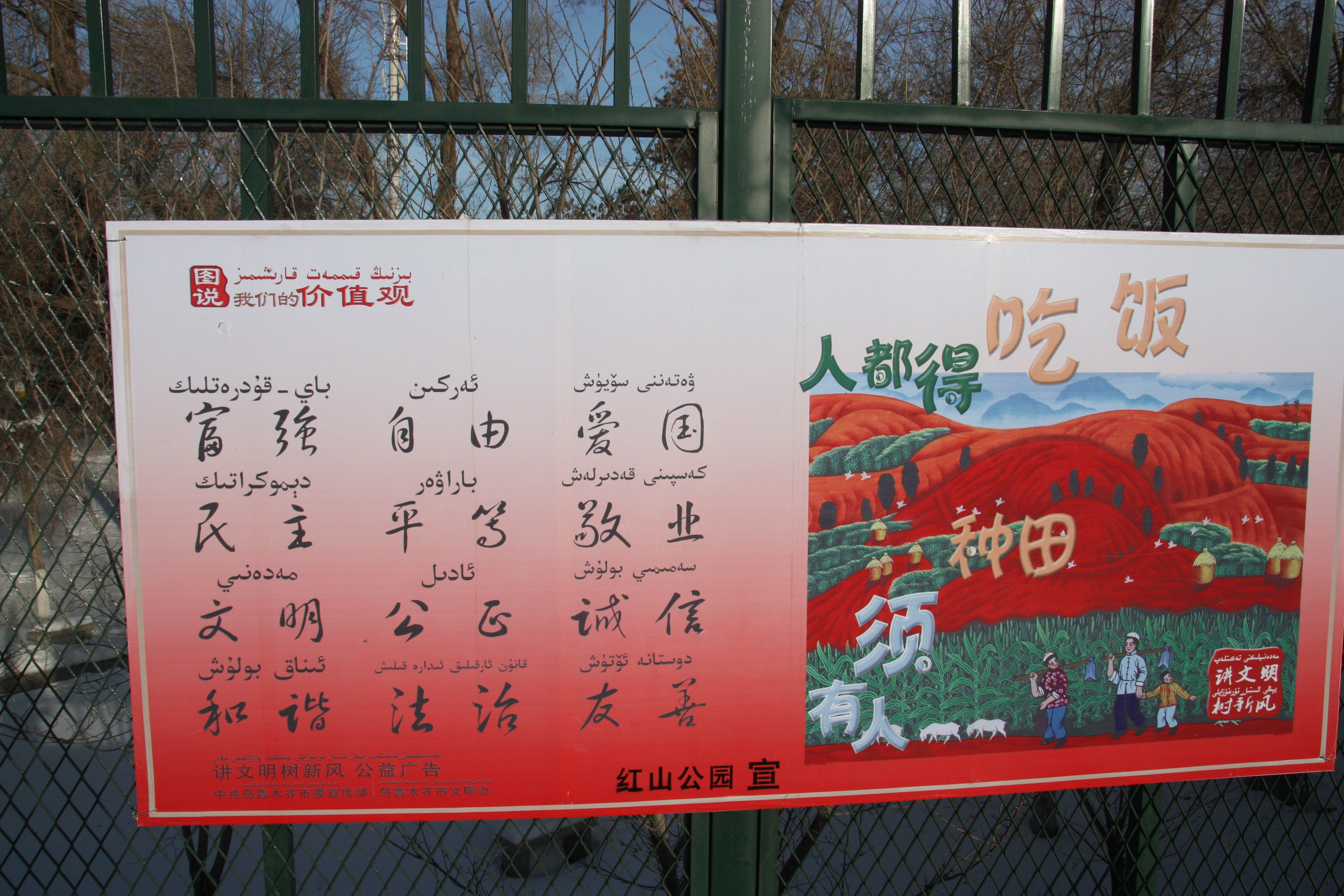

Der Einfluss von den neuen Seidenstraßen auf Zentral- und Osteuropa hat auch potenzielle Folgen für Deutschland und die EU. Die 16+1 Initiative ist ein Versuch, engere Kooperation zwischen China und 16 europäischen Staaten östlich von Deutschland[1] zu entwickeln (CEEC. 2016). China hat drei Prioritäten für wirtschaftliche Kooperation in der Initiative bestimmt: Infrastruktur, Hochtechnologie und grüne Technologie. Geopolitisch gesehen von der EU ist Zentraleuropa ein Axialer Standort. Die Länder östlich von Deutschland sind relativ neue Mitglieder der EU und ehemalige Ostblockstaaten. Von den 16 Ländern in der Initiative sind nur die Balkanländer nicht Mitglieder der EU (Ibid.). Die neue EU Länder sind nicht völlig zufrieden mit ihrer Einstellung in der EU, und man muss fragen, ob die Länder durch politische und wirtschaftliche Einfluss von China weiter von der EU entfernt werden können. Deutschland ist der größte Unterstützer der EU, und eine Belastung der EU ist auch eine Belastung auf Deutschland. Die 16+1 Länder brauchen eine Entwicklung ihrer Infrastrukturen, und China will dieselbe Entwicklung, um die Neuen Seidenstraßen zu verwirklichen. Diese gegenseitigen Ziele baut Chinas politisches Gewicht in der Region aus, weil China bereit ist, für die Neuen Seidenstraßen zu investieren. Der erste 16+1 Gipfel ist im Jahre 2012 stattgefunden (CEEC), vordem die neuen Seidenstraßen angekündigt wurden. 16+1 ist deswegen ein Beispiel von einem alten Projekt, das später unter den Namen Seidenstraße hingebracht wurde. Diese Änderung der Markenpolitik von bestehenden Initiativen ist eine der Methoden, die angewendet wird, um Ein Gürtel und eine Straße zu erweitern, ohne genügend Kapital zu haben. Durch diese Methode hat eine Konzeptualisierung der Neuen Seidenstraßen sehr schnell über Eurasien durchquert. Sie setzt aber voraus, dass bestehende Initiativen freiwillig Teil der Neuen Seidenstraßen werden wollen. Abgesehen von der Perspektive von bestehenden Initiativen, nimmt die chinesische Regierung an, dass alle Logistik- und Infrastruktur Projekte entlang der Neuen Seidenstraßen automatisch Teil von der chinesischen Initiative ist.

Deutschland befindet sich in einer guten geographischen Lage, um einen wichtigen Punkt auf den Neuen Seidenstraßen zu werden. Es ist aber nicht das einzige Land in Europa, das wichtig für die Verwirklichung der Initiative ist. Duisport ist von besonderer Bedeutung wegen seiner Position am Rhein und seiner Rolle als Logistiker, der schon mit China angebunden ist. Effizienz von Bahnverkehr bestimmt den Erfolg der Initiative, und Ein Gürtel und eine Straße kann nur gelingen, wenn die logistische Infrastruktur über Eurasien entwickelt wird. Das hat aber politische Folge in Europa, weil China Einfluss auf Regionen wie Osteuropa und Griechenland durch Entwicklungspläne nehmen könnte. Das stellt eine mögliche Belastung auf die EU und bestehenden Institutionen in Europa dar.

Kapitel 3 – Duisport und Volkswirtschaft

Logistik und Geopolitik können nicht getrennt werden. „Ein Gürtel und eine Straße“ ist eine Kombination von geopolitischen Projekten, sowie Handels- und politische Beziehungen, und Geopolitik und Volkswirtschaft müssen zusammen in Betracht gezogen werden, um die Bedeutung des Projektes zu evaluieren. Analyse von nur geopolitischer Positionierung zeigt nur Wirkung und nicht Ursache. Eine Analyse von Volkswirtschaft entdeckt die Ursachen der geopolitischen Wirkungen, die im zweiten Kapitel vernachlässigen lässt. Durch Diskussion von sowohl Ursachen (Volkswirtschaft), als auch Wirkung (Geopolitik), kann man den Einfluss von den neuen Seidenstraßen in Deutschland besser verstehen.

Es besteht eine große Diskrepanz zwischen Kommentar und Akteuren von den Neuen Seidenstraßen in Deutschland. Im Letzten Kapitel lässt es sich zeigen, dass einige Unternehmen zugunsten des Projekts reagieren, und beginnen „Einen Gürtel und eine Straße“ als Chance zu nutzen, um auszubauen. Beteiligt sind aber bisher hauptsächlich Logistikunternehmen. Im Bereich Politik hat Angela Merkel und Sigmar Gabriel offiziell das Projekt gelobt, solange es internationalen Bedingungsrahmen und Institutionen folgt. Die Beziehungen zwischen diesen Akteuren und dem chinesischen Projekt werden in diesem Text als sozial konstruierte Institutionen betrachtet, und lässt sich auf Alexander Wendts Verständnis von Konstruktivismus stützen, um Die Beziehungen zu analysieren. Um die deutschen Reaktionen über die Neuen Seidenstraßen zu kontextualisieren, muss man zunächst die Politik der chinesischen Seite tiefer eingehen. Nützliche Quellen dafür sind Visionen und Aktionen zum gemeinsamen Aufbau des Wirtschaftsgürtels entlang der Seidenstraße und der maritimen Seidenstraße des 21. Jahrhunderts und Gespräche von Präsidenten Xi Jinping.

Die Kernideen haben sich seit der Ankündigung des Projekts im Jahre 2013 nicht viel verändert. Damals wurden die Förderung von politischen Kommunikation, die Verbesserung von Verkehr, die Erleichterung von Handelsrouten und verbesserte Zusammenarbeit zwischen Ländern betont (Xi. 2013). Im Vergleich zu dem im Jahre 2015 geschriebenen Visionen ist eine Veränderung nicht zu sehen (staatliche Kommission. 2015). Deutschland sollte damit ermutigt werden. Obwohl der vollständige Plan, der Deutschland sehen möchte, ist nie zustande gekommen, besteht es Kontinuität hinsichtlich der Konzeptualisierung der Neuen Seidenstraßen. Auch in Xis Gesprächen im Jahre 2017 bei dem nationalen Volkskongress sind die Kernpunkte fast identisch, aber mit dem Zusatz von einer Förderung zur Erschaffung eines neuen internationalen Kooperationsplatform (Xi. 2017a). Dadurch handelt China die implizite deutsche Anschuldigung ab, dass China internationale Normen nicht folgt. Diese Anschuldigungen werden später diskutiert. Die Veränderung sollte ernst genommen werden, da sie bei dem wichtigsten innenpolitischen Treffen in China erschien. Was erst bei dem nationalen Volkskongress erscheinen lässt, stellt oft die wichtigsten Entscheidungen der chinesischen Regierung dar.

Die Kernideen des Projekts sind volkswirtschaftliche Ziele mit einer konstruktivistischen Prägung.

Von der konstruktivistischen Perspektive Wendts sind Identitäten und Interessen durch entwickelnde Kooperation und Wandel von egoistischen Identitäten in kollektiven Identitäten durch internationale Mühen transformiert (Wendt. 1992 s.395). Die chinesische Wahrnehmung des internationalen Systems mit Blick auf die Neuen Seidenstraßen entspricht dem Verständnis Wendts. Internationale Kooperation wird durch internationale Institutionen durchgeführt. Die EU ist zum Beispiel in groben Zügen die europäische Institution zur internationalen Kooperation, und ASEAN ist mittlerweile das ostasiatische Gegenstück dafür. Die Förderung von einer verbesserten Verteilung von Ressourcen repräsentiert einen Versuch, Identitäten und Interessen von Staaten durch fairen Handel zu vereinen. In Kombination mit der Integration von Märkten entspricht die wahrgenommene Vereinigung von Identitäten und Interesse dem Glaube, dass Handelsnationen friedliche Nationen sind. Dieser Glaube hat Deutschland und Europa sehr erfolgreich gedient. Der Vorläufer der EU, die Europäische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, wurde teilweise gegründet, um künftige kriege zu vermeiden, und in der Geschichte der EU ist kein Krieg zwischen EU Mitgliedern passiert. Chinas Förderung von Integration von Märkten und verbesserten Verteilung von Ressourcen ist deshalb das Streben nach einem friedlichen internationalen System, in dem Identitäten und Interesse nicht aggressive nationale Egoismen sind. Deutschland und China unterstützen daher eine ähnliche Wahrnehmung der internationalen Ordnung, in der Frieden durch Institutionen und multilaterale Zusammenarbeit durchgeführt wird. Deutschland verdächtigt trotzdem chinesische Interessen. Das ähnliche Verständnis des internationalen Systems von China und Deutschland ist offenbar nicht genügend, ohne Verdacht zusammenzuarbeiten, und das deutet auf gegenseitige sozial konstruierte Wahrnehmungen hin.

Ein Beispiel dafür ist das Wort Inklusivität (baorongxing). Inklusivität war seit dem Anfang des Projekts ein wichtiges wiederkehrendes Wort, aber Xi hat bei dem 2017 Einem Gürtel und einer Straße Gipfeltreffen Inklusivität viel mehr als früher betont (Xi. 2017b). Ein Standpunkt, der Inklusivität betont, darf untypisch von China erscheinen, da das Land bekannt für eine Geschichte von geschlossenen Grenzen und Geheimhaltung ist. China hat aber seit den Wirtschaftsreformen der 70er Jahren allmählich wirtschaftlich geöffnet und liberalisiert. Die Neuen Seidenstraßen zeigen Chinas Absicht und Fähigkeit, die wichtigsten Akteuren der Weltwirtschaft beizutreten, und die Weltwirtschaft benötigt Handel, den wiederum offene, inklusive multilaterale Beziehungen benötigt. Inklusivität entspricht daher dem Ausbau von internationalen Strukturen, die gegenseitige Gewinne fördern. Das Wort steht aber nicht vollständig für Offenheit und Zusammenarbeit. Ein ganzes Teil seines Gesprächs wurde Inklusivität gewidmet, in dem die alte Seidenstraße als ein historisches Beispiel von Inklusivität dargestellt wurde. Dadurch werden Indien und die zentralasiatischen Länder als notwendige Punkte entlang der Straße genannt (Ibid.). Auf diese Weise lässt China eine aggressive Seite von Inklusivität zeigen, die teilweise Mitgliedschaft diktiert. Kein Land muss offiziell teilnehmen, aber Xi verdeutlicht, dass viel Drück auf Länder in der Nähe von China liegt.

Visionen Verbirgt auch Bedingungen über das Mandat der Chinesen. Visionen führt fünf Prinzipien der friedlichen Koexistenz ein, und davon enthält die gegenseitige Nichteinmischung in die inneren Angelegenheiten (Staatliche Kommission. Op. Cit.). Das zeigt, dass China selbst nicht bereitwillig ist, vollständig international zusammenzuarbeiten. Chinas innenpolitischen Angelegenheiten werden oft von westlichen Ländern kritisiert. Westliche Länder kritisieren zum Beispiel oft Menschenrechte und politische Freiheit in China, und eine Förderung von Nichteinmischung in die inneren Angelegenheiten sollte als Versuch betrachtet werden, solche Kritik umzuleiten. Das steht auch für die schwierigen politischen Beziehungen mit Hong Kong und Taiwan. Als innere Angelegenheiten sollte die internationale Gesellschaft nichts mit der Ein-China-Politik zu tun. Das hat Implikationen dafür, wie die internationale Politik mit China funktioniert, da die Ein-China-Politik von zentraler Bedeutung in internationalen Beziehungen mit China ist, und eine Veränderung in der aktuellen Politik würde ostasiatische multilaterale Beziehungen bedrohen. Dieser Faktor ist im eigenen Interesse der chinesischen Regierung, und zeigt, dass das chinesische Projekt verantwortungslose Gewinne will. Der Standpunkt des deutschen Auswärtigen Amts steht im Gegensatz zu den Prinzipien der friedlichen Koexistenz, da es „China innenpolitisch weiter entwickeln [will]“ mit „entwickelten Rechtstaatlichen Strukturen, politischer und ökonomischer Gerechtigkeit und Freiheitsrechten“ (Auswärtiges Amt. 2017). Das Auswärtige Amt darf nicht dieses Konzept akzeptieren, ohne ihre eigene Politik zu widersprechen. Es sollte die Prinzipien der friedlichen Koexistenz nicht akzeptieren, weil sie Menschenrechte und Freiheit in China nicht gewährleisten.

Furcht in Deutschland vor eine Veränderung in der Weltordnung wegen der Neuen Seidenstraßen ist deutlich zu sehen. Außenminister Sigmar Gabriel hat bei der 25. Französischen Botschafterkonferenz klar gemacht, dass er eine Veränderung des geopolitischen Standpunkts von Europa fürchtet. Er weist darauf hin, dass Amerika sich zunehmend an Asien statt Europa richtet (Gabriel. 2017b). Laut Gabriel zeigt die Veränderung, dass Europa weniger bedeutsam wird, während die übrige Welt wächst. (Ibid.) Sein Standpunkt ist aber übertrieben. Amerika und Europa haben noch starke Beziehungen, und die größte Belastung auf den aktuellen Beziehungen ist nicht China, sondern die Unberechenbarkeit des aktuellen Präsidenten. Gabriel ist jedoch überzeugt, dass „Wenn es [Europa] nicht gelingt, eine eigene Strategie mit Blick auf China zu entwickeln, dann wird es China gelingen, Europa zu spalten“(Ibid.). Er verwendet 16+1 als Beispiel dafür, wie China schon versucht, Europa zu spalten, aber seine Behauptung ist nicht stichhaltig. Er behauptet, dass Chinas Name für die Initiative, 1+16 statt 16+1, die diktatorische Einstellung von China in der Gruppe abbildet. Die Mehrheit von chinesischen Texten verwenden aber 16+1 genau wie europäische Quellen. Gabriels Furcht vor eine Spaltung von Europa entlang der 16+1 Grenze ist aber nicht unbegründet. Die neue EU Länder sind unzufrieden mit ihren Einstellung in der EU, und wenn China eine bessere Option anbietet, dann könnte Osteuropäischen Ländern sich selbst entscheiden, engere Beziehungen mit China zu entwickeln. China führt dennoch keine aggressive Politik, um diese Möglichkeit eine Gewissheit zu machen. Man muss berücksichtigen, dass Ein Gürtel und eine Straße keine exklusive Initiative ist. Kein Land muss die EU verlassen, um in dem chinesischen Projekt teilzunehmen. China will kein neues Modell für die internationalen Ordnungstrukturen. Godehardt stimmt zu und stellt fest, dass China Mechanismen der heutigen Ordnung folgt, und dass China auch in internationalen Netzwerke eingebunden ist (Godehardt. 2016a. s.35). Da China in der bestehenden Strukturen integriert wird, ist es dabei abhängig von einer stabilen Weltordnung. Eine Spaltung von Europa, wie Gabriel fürchtet, würde die neuen Seidenstraßen beschädigen.

Duisport anerkannt eine Veränderung der internationalen Ordnungsstrukturen auch und reagiert positiv darauf. Während China eine Liberalisierung des internationalen Wirtschaftssystems fördert, positioniert Duisport, um diese Vorstellung vollständig auszunutzen (Duisport. 2016b). Duisport betont die neue Führung in Amerika und die Unsicherheit in Europa nach dem Brexit als Gründe dafür, enger mit China zusammenzuarbeiten (Ibid.). Duisport stimmt offenbar mit Sigmar Gabriels Behauptung zu, dass Europa allmählich schwächer wird, und daher außerhalb von Europa blicken muss, um seinen Geschäftsbetrieb zu erweitern. Das erklärt, warum Duisport seinen Geschäftsbetrieb nach Osten verschiebt. Die neue Zentren des Unternehmens in der Türkei (Duisport. 2016b. s.90) und Zusammenarbeit in Triest (Ibid.) sind näher am asiatischen Markt, und deshalb besser positioniert, Warenverkehr in die EU zu kontrollieren, insbesondere während die Landrouten noch nicht weit entwickelt sind. Die Neuen Seidenstraßen versuchen ein internationales ökonomisches Netzwerk zu schaffen, und Duisport Reagiert darauf mit seinem eigenen Netzwerk entlang der Routen, damit es eine möglicherweise geschwächte Europa gleichzeitig unterstützen und davon profitieren könnte. Duisport sieht Die neuen Seidenstraßen als eine große Chance Geschäftsbetrieb weiter zu entwickeln, und einige Faktoren des volkswirtschaftlichen Hintergrunds sehen vorteilhaft für Duisport aus. Deutschland ist Chinas wichtigste Handelspartner in Europa, während China der wichtigste Handelspartner Deutschlands ist (Auswärtiges Amt. 2017). Handelsvolumen zwischen China und Deutschland im Jahre 2016 hat 169,9 Mrd. Euro erreicht (Ibid.), und China sieht Deutschland als Schlüsselpartner in Europa (Ibid.). Es gibt dazu über 60 Dialogmechanismen zwischen China und Deutschland, und viele davon sind auf hoher Regierungsebene (Ibid.).

Die enge Verbindung zwischen der Politik und dem Unternehmen in Deutschland ist wichtig dafür, wie sich internationale Beziehungen hinsichtlich des chinesischen Projekts entwickeln werden. Duisports 300 Jahre Hafenjubiläum zeigt die Signifikanz dieser Beziehung. Viele wichtige Politiker haben teilgenommen. Schröder und Merkel wurden eingeladen, aber mussten kurzfristig wegen einer Brexit-Handlung absagen. Wolfgang Klement, Alexander Dobrindt, und Sigmar Gabriel waren aber bei dem Hafenjubiläum (Duisport. 2016b. s.32-35). Das zeigt die innenpolitische Bedeutung des Hafens. Darin existiert das Potenzial, China politischer Einfluss in die deutsche Politik auszuüben. Wenn Duisport zunehmend chinesische Interessen Aufmerksamkeit schenkt, übt China einen politischen Einfluss zurück aus. Das könnte wiederum durch die Verbindung zwischen Duisport und die deutsche Politik dazu führen, dass China auch Einfluss auf die deutsche Innenpolitik hat. Für Gabriel war der 300 Jahre Fest nicht der einzige Besuch bei Duisburger Hafen.

Es ist nicht nur die deutsche Politik, sondern auch die chinesische Politik, die Interesse an Duisport zeigt. Chinas wichtigste Zeitung und Sprecher der Regierung People‘s Daily weist auf Duisport als wichtigen Punkt auf den Neuen Seidenstraßen hin (Renmin Ribao. 2014a). Sie erzählt Duisport genau wie das Unternehmen selbst als wichtigster Innenhafen Europas, und betont die Bedeutung des Unternehmens für die Verbesserung sino-deutscher Beziehungen (Ibid.). People’s Daily ist so eng verbunden mit der chinesischen Regierung, dass jeder Satz die offizielle Meinung der kommunistischen Partei ausdrückt. Daraus lässt sich ableiten, dass Duisport von der chinesischen Regierung als wichtiger Punkt auf den Neuen Seidenstraßen betrachtet wird. People’s Daily sagt, dass Duisport nicht nur wirtschaftlich Signifikant ist, sondern auch politische Bedeutung hat (Ibid.) Das gibt Anlass zur Sorge, weil es eine Anerkennung repräsentiert, dass China politisches Gewicht über Duisport verfügt. Auch Cosco hat die geopolitische Bedeutung von Duisport anerkannt (Cosco. 2017b). Da Cosco ein chinesisches staatseigenes Unternehmen ist, sollte man die Anerkennung auch als politisch bedeutsam betrachten. Es ist jedoch mit den verfügbaren Quellen schwer zu sagen, inwiefern einen greifbaren politischen Einfluss von China bei Duisport existiert. Es ist dennoch deutlich, dass China Duisport sowohl von einer Wirtschaftlichen, als auch einer politischen Perspektive betrachtet.

Duisport ist allmählich wichtiger für kulturelle Beziehungen zwischen Deutschland und China geworden, und Kultureller Austausch ist auch politisch geprägt. Schüller und Nguyen weisen darauf hin, dass kulturelle Austausch und Veranstaltungen Beispiele von Soft-Power sind (Schüller & Nguyen. 2015, s.2). Beispiele von Soft-Power wie internationale Kulturelle Veranstaltungen oder Organisationen (wie das Konfuzius-Institut) verändern internationale Identitäten sowohl auf der politischen Ebene, als auch auf der Basisebene. China versucht kultureller Austausch, als Mittel Kooperation zwischen China und Deutschland zu vertiefen, und Grenzen zu erleichtern. Laut Xi Jinping ist kultureller Austausch ein wichtiges Element der Neuen Seidenstraßen, weil er zu engeren Kooperation führt (Xi. 2017b). Duisport hat von einem Anstieg in kulturellen Austausch zwischen China und Deutschland schon viel profitiert, weil es eine Schlüsselrolle in der Transportierung von Kunst zwischen den zwei Ländern für die Kunst Veranstaltungen Deutschland 8 in China und China 8 in Deutschland hatte (Duisport. 2017c). Deutschland 8 wurde die größte Ausstellung von deutschen Kunst in China (Ibid.), und ist in der verbotenen Stadt in Beijing stattgefunden (Gabriel. 2017c). Der Veranstaltungsort ist höchst symbolisch, und stellt in Kombination mit der Größe der Veranstaltung eine besondere Beziehung zwischen den zwei Ländern. Es ist nur in der jüngeren Geschichte, dass China aus der Reste der Welt verschlossen wurde, aber China hat den Standort, der früher der geschlossenste im Land war, für kulturellen Austausch geöffnet. Duisport behauptet, dass seine Rolle als Versender von der deutschen sowie der chinesischen Regierung unterstützt wurde, und betont die Verbindung zwischen dieser Ausstellung und die Neuen Seidenstraßen. Es stimmt, dass der Gebrauch von Bahnverkehr über Eurasien für die Transportierung von Kunst stellt einen Beispiel von den Neuen Seidenstraßen Zielen dar. Es symbolisiert unter anderem Kooperation, Zusammenarbeit, und Austausch zwischen Deutschland und China, sowie zwischen den Ländern, die die Routen überqueren müssen, um die Transportierung zu ermöglichen. Duisports Meinung spiegelt Xis Standpunkt darüber, wie Deutschland und China gegenüber die Neuen Seidenstraßen zusammenarbeiten sollen, nämlich in den Bereichen „Kultur, Bildung, Jugendliche, Thinktanks, Medien, Tourismus, Fußball und die Zusammenarbeit auf lokaler Ebene“ (Bundesregierung. 2017).

Außenminister Gabriel hat an der Deutschland 8 Veranstaltung in Beijing und an China 8 in Deutschland teilgenommen (Gabriel. 2017c). Das zeigt, dass die deutsche Regierung die politische Bedeutsamkeit von kulturellen Austausch anerkennt. Gabriel sagte, dass die Veranstaltungen „eine besondere Symbolik für die moderne Seidenstraße“ hatten, insbesondere weil eine Zeremonie für China 8 im Duisburger Innenhafen stattgefunden ist (Ibid.). Dadurch anerkennt Gabriel, wie wichtig deutsche Unternehmen für die Neue Seidenstraßen sind. Es besteht aber eine Diskrepanz zwischen Gabriels Aussage bei Deutschland 8 und 17 Tage zuvor bei der 25. Französischen Botschafterkonferenz. Bei der Botschafterkonferenz hat Gabriel seine Fürchte vor die Initiative ausgedrückt, aber nur zwei Wochen später sprach Gabriel, als ob er die Neuen Seidenstraßen stark unterstützte. Gabriel zweifelt offenbar an der Initiative. Seine Aussage in Frankreich ist mit großer Wahrscheinlichkeit ehrlicher als in Beijing, weil Deutschland und Frankreich engere politische Partners als Deutschland und China sind. Sie sind starke Unterstützer der EU, und Betreuer der bestehenden Weltordnung. Ihre politischen und wirtschaftlichen Prioritäten liegen innerhalb der EU und mit der Aufrechterhaltung von europäischen Institutionen. Die deutsche Regierung muss aber versuchen, gute Beziehungen mit ihrem größten Handelspartner außerhalb der EU zu behalten. Die Diskrepanz zwischen Gabriels Gesprächen ist die Folge davon, der Bedarf, eine Balance zwischen Aufrechterhaltung der EU Institutionen und eine positive Entwicklung der Neuen Seidenstraßen für Deutschland zu fördern.

Protektionismus und Handel Sanktionen sind große Herausforderungen zur bilateralen Beziehungen zwischen China und Deutschland. Dumpingpreise und illegale Subventionen bei chinesischen Photovoltaikpaneelen hat früher zu Streit mit China geführt, was Vertrauen in Chinesische Handelsbeziehungen beschädigt hat (Erber. Op. Cit.). Man kann dadurch verstehen, warum die deutsche Regierung glauben könnte, dass China internationale Normen auf der Neuen Seidenstraßen nicht folgen wird, und warum sie eine verhaltene Einstellung gegenüber der wirtschaftlichen Faktoren der Initiative hat. Das China International Investment Promotion Agency wirft aber vor, dass Deutschland nach einer Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung immer protektionistischer wird. Es behauptet, dass Deutschland Investitionsinteressen von Unternehmen aus Nicht-EU Ländern beeinträchtigt und das deutsche Invesititionsumfeld verschlechtert (China International Investment Promotion Agency. 2017). Es stimmt, dass protektionistische Richtlinien attraktiv sein könnten, weil China sich ständig in Industrien verbessert, die Schlüssel Industrien der deutschen Wirtschaft sind, wie in den Auto- und Energieindustrien. Die deutsche Autoindustrie hat früher eine starke Marktposition in China, aber Nachfrage für deutsche Autos sinkt jetzt, während die chinesische Autoindustrie wächst. (Erber. Op. Cit.) Die Veränderung in komparativen Vorteil in der Autoindustrie ist möglicherweise einer der Gründen für wachsende deutsche Protektionismus. Deutsche Autos sind aber in China noch gefragt (Ibid.), und protektionistische Maßnahmen sind deswegen nicht notwendig. Duisport könnte selbst mit Blick auf die Autoindustrie von protektionistischen Maßnahmen negative beeinflusst werden, da Duisport sich auf Automobil-Logistik nach China konzentriert. Duisport und andere deutsche Logistiker benötigen leichtere Handelskontrolle und Zolltarifs, um effektiv internationale Logistik zu behandeln

Man muss fragen, ob die Neuen Seidenstraßen wirklich wirtschaftlich sinnvoll für Deutschland sind. Laut einem Bericht in South China Morning Post sind die Potenziale Kosten viel höher als das verfügbare Geld in der Asiatischen infrastruktur-Investitionsbank (AIIB) (Holland. 2017), und daher nicht durchführbar. Die AIIB ist aber nicht die einzige Quelle von Finanzierung für die Neuen Seidenstraßen. Der Seidenstraßefonds, der Neuen Entwicklungsbank und der Export-Import Bank of China leisten auch finanzielle Unterstützung (Xi. 2017b). sie tragen jeweilig 100 Milliarde, 250 Milliarde, und 130 Milliarde Renminbi zum Projekt bei (Ibid.). Die Größe der Initiative benötigt aber einen enormen Finzanzierungsaufwand. Godehardt stimmt zu, und glaubt, dass China die Initiative allein nicht umsetzen kann (Godehardt. 2016, s.36). Allein scheint aber nicht der Plan zu sein. China betrachtet existierende Infrastrukturprojekte, die auf den Neuen Seidenstraßen liegen, als Teile der Initiative. Durch Anbindungen zwischen existierenden Projekten wie 16+1 werden Kosten erheblich reduziert. Zusammenarbeit ist nicht nur ein Ideal der Initiative, sondern auch eine Notwendigkeit, um sie zu vollenden. China verfügt über viel Geld für das Projekt, aber ist letzendes abhängig von anderen Ländern. Wie wirtschaftlich sinnvoll die Neuen Seidenstraßen sind, hängt deshalb von einer Vertiefung von internationalen Vertrauen und wirtschaftlichen Institutionen. Problematisch dabei ist der AIIB. Von der deutschen Perspektive repräsentiert der AIIB eine Spaltung in dem bestehenden internationalen Wirtschaftssystem. Deutschland ist der größte nicht-asiatische Anteilseigner der AIIB (Merkel, 2015), aber nicht vollständig aus Überzeugung und Vertrauen. Merkel hat im Jahre 2015 angekündigt, dass Deutschland der AIIB beigetreten ist, „weil [die deutsche Regierung] [ihre] Überzeugung gefolgt [ist], dass China bestehenden Institutionen und Organisationen gebührend berücksichtigt werden muss“ (Ibid.). Dabei versucht die deutsche Regierung, als Gegenkontrolle für die AIIB zu dienen, und sie zeigt ihren Mangel an Vertrauen in die Chinesische Entscheidung, neue internationale Wirtschaftsinstitutionen zu entwickeln. Als eine Initiative, die aus Vertrauen aufgebaut ist, repräsentiert Misstrauen gegenüber der AIIB eine potenzielle Abbremsung der Entwicklung der Initiative. Die deutsche Regierung hat aber recht, die AIIB mit einem gewissen Misstrauen zu betrachten, weil neue internationale Institutionen denselben Richtlinien als die bestehenden Institutionen folgen sollen. Gegenkontrollemechanismen sind nicht eine vollständige Ablehnung der AIIB, sondern eine Art von skeptischen Teilnahme, die notwendig für die Verwaltung von Institutionen sind. Die deutsche Regierung hat jedoch durch ihre angekündigte Absicht ihren besonderen Verdacht auf die AIIB klar gemacht, selbst wenn sie Anteileigner ist.

Die Neuen Seidenstraßen folgen Land- und Seerouten, und es lässt sich bestreiten, ob Schiff- und Bahnverkehr wirtschaftlich sinnvoll sind. Luftfracht ist zum Beispiel viel schneller als Schiff- und Bahnverkehr. Luftfracht von Westchina nach Deutschland dauert 3 Tage, während die Landroute 14 Tage und die Seefracht 45 Tage dauert (Holland. 2017). Luftfracht ist dennoch viel teurer, während Seefracht trotz der langen Zeitaufwand am günstigsten ist. Die neuen Handelsrouten sind daher ausschließlich vorteilhaft für den Verkehr von unverderblichen Waren. Das stellt kein großes Problem für die größten deutschen Industrien wie die Autoindustrie, die von einer langen Zeit bei Transport wenig Wert verliert. Das ist auch der Meinung von Duisport. Industrielle Automobillogistik funktioniert nicht durch Luftfracht wegen der Größe eines Autos. Der deutsche Markt profitiert deswegen von ausgebreiteten Bahnverkehr ungeachtet normaler Vorteilen von Luftfracht über Bahnverkehr, weil die Autoindustrie so wichtig für den deutschen Markt ist. Der Transportierung von Autos durch Bahnverkehr könnte auch durch technologische Fortschritte optimiert werden. Duisport hat begonnen, Hellman-Box Technologie anzuwenden, die eine Kapazitätserhöhung von der Transportierung von Autos ermöglicht (Duisport. 2017a. s.11). Es lässt sich schon nicht leugnen, dass sich der Bahnverkehr zwischen China und Deutschland sehr schnell entwickelt. Über 1200 Züge wurde auf der Verbindung zwischen West-China und Westeuropa gezählt (Duisport. 2017a. s.13), und laut Duisport wurde rund 25 Züge in der Woche in Duisburger Hafen abgefertigt. Das bedeutet, dass die Mehrheit von den gezählten Zügen durch Duisport gefahren sein müssen. Man kann erwarten, dass die Zahl ständig steigen wird.

China will kein neues Modell für die internationalen Ordnungstrukturen. Die Neuen Seidenstraßen sind abhängig von einer stabilen Weltordnung, um die Initiative zu verwirklichen. Die Bedeutung von der Autoindustrie in Deutschland macht eine Entwicklung von Landrouten über Eurasien vorteilhaft, weil die Transportierung von Autos einfacher mit Bahnverkehr als mit Luft- oder Schiffverkehr ist. Eine Entwicklung von Bahnverkehr zwischen Deutschland und China ist besonders vorteilhaft für Duisport, weil es sich auf die Transportierung von Autos konzentriert, und sollte Logistik über Land wirtschaftlich sinnvoller machen. Die Stärke der bestehenden Handelsbeziehung zwischen China und Deutschland bedeutet, dass eine Weiterentwicklung sehr erfolgreich sein könnte, aber die Frage, ob China bereitwillig ist, internationale Normen zu folgen, reduziert das Potenzial, dass die zwei Länder enger zusammenarbeiten werden. Deutschland vertraut die AIIB und chinesische Handelspraktiken nicht, und das Misstrauen könnte zu einer Abbremsung der Entwicklung der Initiative in Deutschland. Ein gewisses Maß an Misstrauen ist aber gerechtfertigt, weil die Initiative Hintergedanken hat, wie der Versuch, internationale Aufmerksamkeit auf Chinas Menschenrechtsbilanz umzuleiten. Die Initiative ist vollständig abhängig von engerer Zusammenarbeit und Kooperation zwischen beteiligten Ländern, und Deutschland und China müssen politische Unstimmigkeiten erlösen, vordem die Neuen Seidenstraßen in Deutschland wirtschaftlich und politisch vorteilhaft für beide Länder werden kann.

Schluss

Die Neuen Seidenstraßen können politisch und wirtschaftlich vorteilhaft für Deutschland sein, aber es muss vorsichtig gegenüber chinesische Hintergedanken sein. Deutsche Unternehmen können von den verbesserten Logistik Infrastruktur gegenüber Eurasien Waren effizienter transportieren, und Logistiker, die Autoindustrie, und E-Commerce haben am meisten zu gewinnen. Die Positionierung von Cosco im Mittelmeer zeigt aber eine aggressive Seite zu Chinas Geopolitik in Europa, und man muss sich erinnern, dass China durch die neuen Seidenstraßen wachsenden politischen Einfluss nimmt. China will die bestehenden Weltordnung Strukturen nicht verändern, aber es besteht das Risiko, dass einige Länder entlang der Neuen Seidenstraßen wie die 16+1 Länder in Osteuropa an China statt alten Partnern in der EU wenden werden. Die internationale Ziele der Neuen Seidenstraße sind meistens in Übereinstimmung mit der internationalen Zielen von Deutschland, aber versteckt sind Ziele, die die deutsche Regierung nicht akzeptieren kann. Furcht vor Einem Gürtel und einer Straße in Deutschland ist nicht unbegründet, aber bleibt trotzdem übertrieben. Deutschland und China müssen ihre politische Vorbehalte lösen, um die neuen Seidenstraßen in Deutschland zu verwirklichen, auf einer Weise, die gegenseitig vorteilhaft ist. Das heißt, internationale Normen und Institutionen müssen berücksichtigt werden, Menschenrechte und Freiheiten müssen in China nicht vernachlässigt werden, und protektionistische Maßnahmen entlang der neuen Handelsrouten sollten vermeidet werden.

Bibliographie

Primärquellen

Die Bundesregierung. 2017. Pressestatements von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel und dem chinesischen Staatspräsidenten Xi Jinping. [Pressemitteilung]. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.bundesregierung.de/

Cosco. 2017a. 中远海运控股股份有限公司2017年半年度报告. 中远海运控股股份有限公司. [Abgerufen am 17.11.17]. Abgerufen von: http://cn.chinacosco.com/

Cosco. 2017b. 德国生产线上了中远海运船. [Abgerufen am 13.02.18] Abgerufen von http://cosnews.cosco.com/.

Dbahn.2017.Deutschland-China und zurück. [Abgerufen am 12/02/2017]. Abgerufen von www.deutschebahn.com/de/Konzern/

DHL.2015. Auf scheinen über die Seidenstrasse. [Abgerufen am 12/02/2017]. Abgerufen von https://www.dpdhl.com/content/

Duisport.2013. Large reception for container train from China in the port of Duisburg. [Abgerufen am 12/02/18]. Abgerufen von Presse.duisport.de/en/newsroom/

Duisport. 2016a. Duisportmagazine: Ein Magazin der Duisburger Hafen AG. [Online]. Duisburger Hafen AG. Nr.4, 2016. [Abgerufen am 03/11/2017]. Abgerufen von http://presse.duisport.de/media/

Duisport. 2016b. Grenzenlos:Local, Regional, Global: Geschäftsbericht 2016 der Duisport-Gruppe. [Online]. Duisburger Hafen AG. [Abgerufen am 03/11/2017]. Abgerufen von http://presse.duisport.de/media/

Duisport. 2016c. duisport is expanding its China business “When you are in Duisburg, you are in Europe”. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://presse.duisport.de/zh/newsroom/

Duisport. 2017a. Duisportmagazine: Ein Magazin der Duisburger Hafen AG. [Online]. Duisburger Hafen AG. Nr.2, 2016. [Abgerufen am 03/11/2017]. Abgerufen von http://presse.duisport.de/media/

Duisport. 2017b. 深化杜伊斯堡与义乌 之间的贸易合作. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://presse.duisport.de/zh/newsroom/

Duisport. 2017c. 中国号列车将德国 艺术带到北京. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://presse.duisport.de/zh/newsroom/

Duisport. 2017d. 穿梭在杜伊斯堡港和. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://presse.duisport.de/zh/newsroom/

Duisport.2017e. Close cooperation between Trieste and Duisburg for the Chinese trade. [Abgerufen am 12/02/18]. Abgerufen von Presse.de/en/newsroom

Gabriel, S. 2017a. Rede des Bundesministers des Auswärtigen, Sigmar Gabriel, beim 9. Kulturpolitischen Kongress am 15. Juni 2017 in Berlin. [Online]. Berlin. Die Bundesregierung. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.bundesregierung.de/

Gabriel, S. 2017b. Rede des Bundesministers des Auswärtigen, Sigmar Gabriel, bei der 25. Französischen Botschafterkonferenz am 30. August 2017 in Paris. [Online]. Paris. Die Bundesregierung. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.bundesregierung.de/

Gabriel, S. 2017c. Rede des Bundesministers des Auswärtigen, Sigmar Gabriel, zur Eröffnung der Ausstellung „Deutschland8“ in Peking am 17. September 2017 in Peking.[Online]. Beijing. Die Bundesregierung. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.bundesregierung.de/

Merkel, A. 2015. Rede von Bundeskanzlerin Dr. Angela Merkel im Rahmen des Bergedorfer Gesprächskreises am 29. Oktober 2015 in Peking. [Online]. Beijing. Die Bundesregierung. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.bundesregierung.de/

Xi, J. 2017a. 中国共产党第十九次全国代表大会. [Online]. 18. Oktober, Beijing. [Abgerufen am 19/10/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/

Xi, J. 2017b. 携手推进“一带一路”建设–在“一带一路”国际合作高峰谈论开幕式上的演讲. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 19/10/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/

Xi, J. 2013. 习近平在纳扎尔巴耶夫大学的演讲(全文). [Abgerufen am 02/02/2018]. Abgerufen von: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/.

Sekundärquellen

Anon. 2017b. Beziehungen zu Deutschland. [Online]. Berlin. Auswärtiges Amt. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/

Anon. 2017c. Die neue Seidenstraße ist nicht zu stoppen!. [Online]. Mainz. Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.bueso.de/seidenstrasse

Belguidoum, S. & Pliez, O. 2015. Yiwu: The Creation of a Global Market Town in China. Articulo Journal of Urban Research. [Abgerufen am 03/03/2017]. Abgerufen von http://journals.openedition.org/

BMVI. 2017. Infrastruktur. [Abgerufen am 24/02/18]. Abgerufen von https://www.bmvi.de/

Brzezinski, Z. 1997. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York. Basic Books.

CEEC. 2016. About 16+1. [Abgerufen am 13/03/2018]. Abgerufen von http://ceec-china-latvia.org/.

Central bureau voor de statistiek. 2016. Meer export naar Noordrijn-Westfalen dan naar Frankrijk. [Abgerufen am 24/02/18]. Abgerufen von www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/

China International Investment Promotion Agency. 2017. Kommentar zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung durch die Bundesregierung. [Online]. M&A Dialogue. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.ma-dialogue.de/

Desjardins, J. 2017. 35 Chinese Cities with Economies as Big as Countries. Visual Capitalist. [Abgerufen am 03/03/2018]. Abgerufen von http://www.visualcapitalist.com/

Den Butter, F & Hayat, R. 2008. Trade between China and the Netherlands: A case study of trade in tasks. Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 29/03/18]. Abgerufen von. https://www.emeraldinsight.com/.

Duranton, S, Et.al. 2017. The 2017 European Railway Performance Index. BCG [Abgerufen am 24/02/18]. Abgerufen von https://www.bcg.com/

Ebbighausen, R. 2017. Die deutsche Sicht auf Chinas Seidenstraße. Deutsche Welle. [Online]. 17 Juli. [Abgerufen am 30/09/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.dw.com/de/

Erber, G. 2013. Deutsch-chinesische Wirtschafts-beziehungen: Chancen und Risiken für Deutschland. [Online]. Nr 41.2013. Berlin. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.diw.de/documents/

Gao, S. 2017. 中国“一带一路“工程困难重重. [Online]. Washington DC. Radio Free Asia. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/

Gilpin, R. 2001. Global political economy: understanding the international economic order. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Godehardt, N. 2014. Chinas »neue« Seidenstraßeninitiative: Regionale Nachbarschaft als Kern der chinesischen Außenpolitik unter Xi Jinping. [Online]. Berlin. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. [abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.swp-berlin.org/

Godehardt, N. 2016a. Chinas Vision einer globalen Seidenstraße. In: Perthes, V. Hg. Begriffe und Realitäten internationaler Politik. [Online]. Berlin. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.swp-berlin.org/

Godehardt, N. 2016b. The Chinese OBOR Initiative: An Alternative Concept of International Order? [Online]. Berlin. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von https://www.swp-berlin.org/.

Godehardt, N. Und Kohlenberg, P, J. 2017. Die Neue Seidenstraße: Wie China internationale Diskursmacht erlangt. [Online]. Berlin. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. [Abgerufen am 01/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.swp-berlin.org/

Hanemann, T & Huotari, M. 2015. Chinese FDI in Europe and Germany: Preparing for a New Era of Chinese Capital. [Online]. Mercator Institute for China Studies. [Abgerufen am 27/03/2018]. Abgerufen von http://rhg.com/wp-content/.

HKTDC. 2015. One Belt One Road: Yuxinou Railway Development. [Online]. [Abgerufen am 25/02/2018]. Abgerufen von http://economists-pick-research.hktdc.com/.

Holland, T. 2017. Puffing across the ‘One Belt, One Road’ Rail route to nowhere. South China Morning Post. [Online]. 24 April. [Abgerufen am 01/02/2018]. Abgerufen von http://www.scmp.com/.

Knittlmayer, N. 2016. Germany’s fear of China could see it left behind on the Belt and Road journey. South China Morning Post. [Online]. 14 November. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von http://www.scmp.com/.

Lindblom, C, E. 1977. Politics and markets: the world’s political-economic systems. New York: Basic Books.

Renmin Ribao. 2014a. 习近平参观德国杜伊斯堡港. [Abgerufen am 15/02/18]. Abgerufen von www.duisport.de/media/.

Renmin Ribao. 2014b. 习近平参观德国杜伊斯堡港. [Abgerufen am 15/02/18]. Abgerufen von www.duisport.de/media/.

Glass, D. 2018. Cosco Reveals $620m Pireaus Development Plan. [Online]. Seetrade maritime News. [Abgerufen am 15/03/18]. Abgerufen von http://www.seatrade-maritime.com/news/ .

Schüller, M. und Nguyen, T. 2015. Vision einer Maritimen Seidenstraße: China und Südostasien. [Online]. Nr.7.2015. Hamburg. Leibniz-Institut für globale und regionale Studien. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://www.giga-hamburg.de/

Staatliche Kommission für Entwicklung und Reform. 2015. Visionen und Aktionen zum gemeinsamen Aufbau des Wirtschaftsgürtels entlang der Seidenstraße und der maritimen Seidenstraße des 21. Jahrhunderts. [Online]. Botschaft der Volksrepublik China in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von http://www.china-botschaft.de/

Statista. 2018. Umsatz durch E-Commerce (B2C) in Deutschland in den Jahren 1999 bis 2016 sowie eine Prognose für 2017 (in Milliarden Euro). Statista. [Abgerufen am 10/03/18]. Abgerufen von https://de.statista.com/

Staudinger, H. 2017. So können Anleger an Chinas Mega-projekt „One Belt, One Road“ teilhaben. [Online]. Hamburg. Fonds & Friends Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.dasinvestment.com/

The Guardian. 2017. Welcome to Yiwu: China’s testing ground for a multicultural city. [Abgerufen am 18/02/18]. Abgerufen von https://www.theguardian.com/cities/

The History of Commerce. Kein Datum.“一带一路”倡议的提出. [Abgerufen am 02/02/2018]. Abgerufen von: http://history.mofcom.gov.cn/.

Thumann, M. 2015. Chinas Traum einer neuen Seidenstraße. Zeit. [Online]. 10 Juli. [Abgerufen am 30/09/2017]. Abgerufen von: http://www.zeit.de/Politik/

Van der Putten, F, P. Et al. 2016. Europe and China’s New Silk Roads. [Online]. European Think-tank Network on China. [Abgerufen am 14/04/2018]. Abgerufen von: http://www.iai.it/sites/ .

Vorhölter. D. 2017. Interesse für die „neue Seidenstraße. [Online]. Berlin. OWC Verlag für Außenwirtschaft GmbH. [Abgerufen am 04/11/2017]. Abgerufen von: https://owc.de/.

Wendt, A. 1992. Anarchy Is What States Make It: The Social Construction of Power Politics. The MIT Press. International Organisation. Vol. 46, No. 2. S.391-425.

[1] Einschließlich Albanien, Bosnien-Herzegowina, Bulgarien, Kroatien, der Tschechischen Republik, Estonien, Ungarn, Lettland, Litauen, Mazedonien, Montenegro, Polen, Rumänien, Serbien, Slowakei, Slowenien.

The first sign were the willow trees. Before even the blossom started to appear, cascades of young, lightly coloured leaves began to drape their way across the green spaces.

The first sign were the willow trees. Before even the blossom started to appear, cascades of young, lightly coloured leaves began to drape their way across the green spaces.