As China works day and night to contain the deadly Coronavirus, the world claims the country is not working hard enough. It is becoming clear that much of the global criticism stems from prejudice rather than reason. In fact, we should be praising, not criticising, the response of the Chinese authorities and people.

China has taken unprecedented measures to contain the Coronavirus. The entirety of Wuhan, the city with a population of 11 million at the epicentre of the epidemic, has been placed on lockdown to control the spread of the disease.

As drastic as this measure is, it has no doubt hugely reduced the number of cases and restricted the virus to predominantly one city. 70% of the 37’000 identified cases worldwide have been diagnosed in Hubei province, the region of which Wuhan is the largest city.

The Chinese authorities did not close the city and leave them without support. 1400 military doctors, some with experience working during the SARS and Ebola outbreaks, were posted to the city to aid the local medical staff.

It cannot be denied that placing the whole city under quarantine is creating logistical issues. Resources are limit and medical facilities can no longer support every patient. The city has struggled to keep up supplies of virus testing kits, leaving many people undiagnosed in the hospitals.

Yet the city has gone to extraordinary measures to address the burdened hospitals and built two emergency hospitals in little over a week. Huoshenshan hospital, the first to be finished, boasts a capacity of 1000, whereas Leishenshan hospital can provide for 1500 patients.

It is not only Wuhan that has responded impressively to the Coronavirus outbreak. Even in cities with relatively few cases, the government has requested citizens to not leave their homes unless necessary and the people have listened.

Those who have not followed the rules often find their greatest critics to not be the police, but other citizens. SCMP published a video of a man using a drone to tell off fellow villagers for not using facemasks when outside. My own landlord in Beijing issued a warning that she would evict anyone who left the apartment for any reason other than necessity, so as to protect the families living in the same neighbourhood.

Restricting the movement of citizens is of course a challenge during the world’s largest annual migration of human beings, but that is precisely what China has had to deal with. The most important holiday of the year, Spring Festival, started only a few days after the virus started to spread.

Billions of journeys take place every year during the festival and this year the government predicted that 3 billion trips would be made over the festival. This had the potential to spread the virus at breakneck speed, but its spread was astoundingly widely controlled.

Citizens returning back home to Beijing after Spring Festival were required to register their arrival and where they had been. At the busiest period for returning residents in Beijing, policemen were posted to the vast majority of residential streets to record where residents had been and their health condition.

China is also risking their own economy to bring the virus under control faster. The Spring Festival break was initially extended to 3rd February and businesses were asked to remain closed. Despite the risk to business, especially small family-run businesses, the requests were widely followed.

This is all the more impressive, seeing as the work ban was later extended until the 10th. Many of the businesses that did opt to reopen did so on much shorter working hours.

Other than closing their own borders, there are few measures left for China to take. That is unlikely to happen until it is deemed completely necessary as the economic burden would be too high, both for China and the rest of the world.

Comparing the current Coronavirus outbreak to previous epidemics clearly highlights the effort that China is making this time. During the SARS outbreak in 2003, China did not share information with WHO immediately and it took about 5 months to identify the virus. This time, Coronavirus has already been sequenced and information has been made available worldwide.

When SARS had finally been contained, the number of deaths worldwide had reached nearly 800 and the virus had spread to nearly 30 countries.

Control measures for the 2009 H1N1 outbreak paled in comparison to China’s current measures, a disease which spread to nearly every country on the planet and resulted in a minimum of 18,500 deaths. The US Center of Disease Control estimated in 2012 that cases may have been up to 15 times that figure.

There are meanwhile, in the US alone, 19 million cases of the common flu this year. The flu is debatably lower risk than the Coronavirus as a vaccine is available, but the massive difference in cases highlights the potential a virus has to spread and how impressive it is that coronavirus cases are still low.

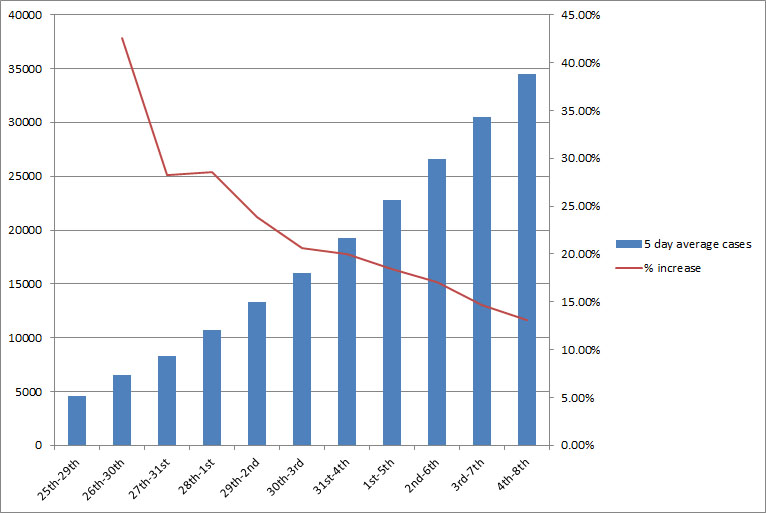

Looking at the figures we should feel hopeful about how long the outbreak will last. Already, the rate of cases is falling. If taken on a daily basis, there have been a number of peaks. New cases rose for example faster on 2nd February. However, taking the average increase over a five-day period, the rate of new cases has steadily fallen and continues to do so. The numbers are clear – China is bringing the coronavirus under control.

Cases in China

Source: JHU CSSE

The rate of new cases outside of China meanwhile is now increasing. A very large proportion of these cases are however stuck in the same confined space – on board the ‘Diamond Princess’, a cruise ship currently moored off Yokohama in Japan. This accounts for 1/6 of all cases outside of China (356 as of 8th Feb). It must be remembered that the tragic spread of Coronavirus on board the ‘Diamond Princess’ is a special situation and not representative – indeed it is much worse – of the spread of the disease outside of China.

Cases outside of China

Source: JHU CSSE

The overly cynical presentation of Coronavirus is however creating serious social issues. Unjustified hysteria is spreading, and Chinese citizens are suffering because of it.

Racism towards Chinese people is increasing because of the virus. It may policy decisions, such as the US’s decision to refuse entry to Chinese passengers at immigration. It may be more explicit, such as businesses in Canada with ‘No Chinese’ signs. The prejudice is clear in videos circulating the internet, showing the ‘disgusting’ food that Chinese allegedly eat. The intended message is clear.

The world should be banding together against the Coronavirus, not turning against the country suffering the most from the outbreak and working the hardest to contain it.